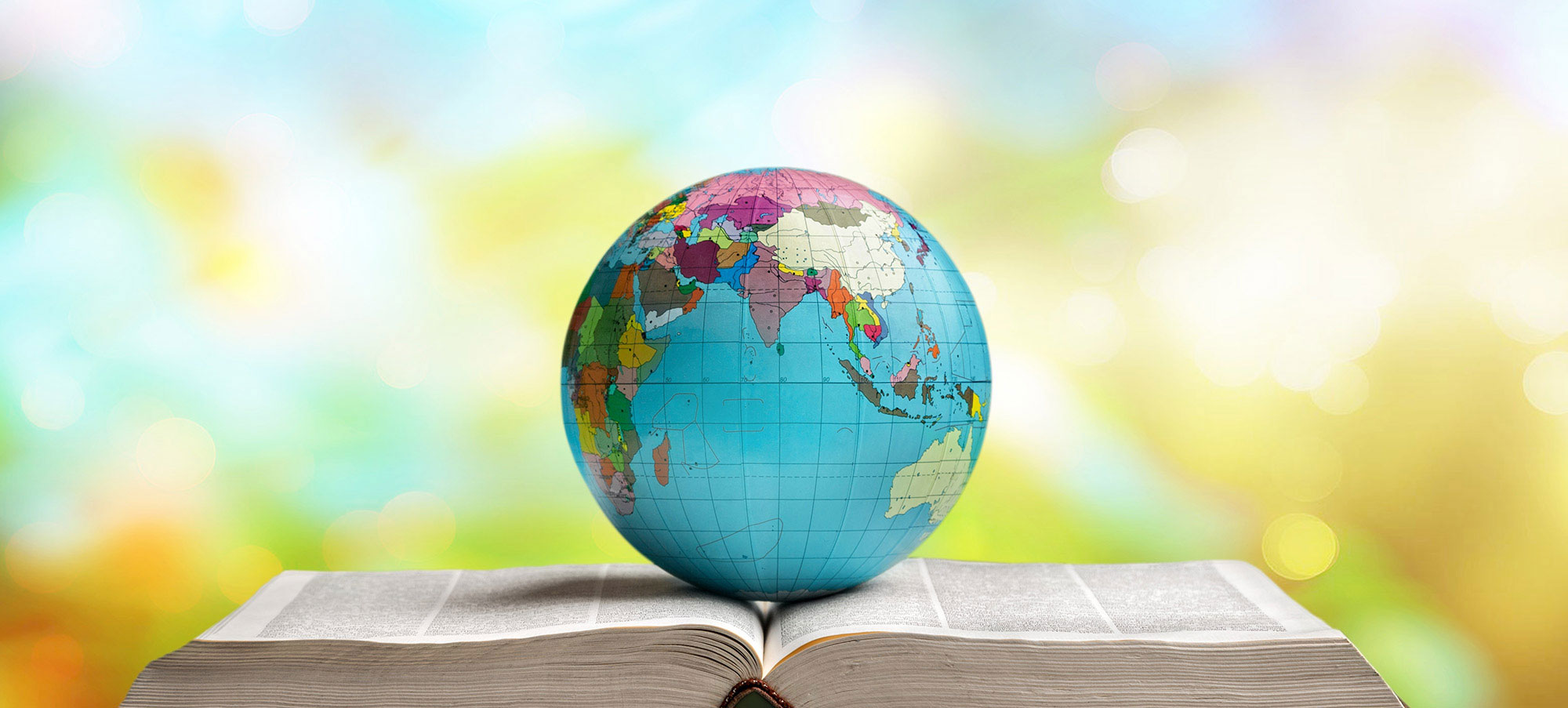

Eric Vanhaute, professor of World History at the Belgian University of Ghent, and Claudia Bernardi, Political Science researcher and lecturer at the Italian University of Roma Tre, co-authored the brand new Global Geo-History Textbook for the Get Up and Goals! project.

DOWNLOAD HERE THE GEO-HISTORY TEXTBOOK

We have met with Mr. Vanhaute to ask a few questions about the book, its aims and the reason why there is a need for a change of perspective.

Enjoy the interview below!

Eric, why it’s important to write a global geo-history book?

There are two very important arguments to me.

Firstly, global history is always also a history of your own time. It includes yourself, your own community, who you are, what you think. So, you become part of history because even in writing it you are part of that meaning. From the very start, global history interrogates your place in the story. So, it’s critical towards yourself, towards your saying and, as I feel it, it’s more critical than established histories, in saying that all the questions we ask, the methods we follow, the storyline we build are just one of the possible questions, methods, storylines. Global history is never neutral. No history is neutral, but they just don’t discuss that.

And the second important thing is that global history is also a non-centric history. It does not put a certain time or place as the privileged starting point from which we would look to the rest of the world. You question the fact that many histories start from a certain place or they take that for granted. Global history doesn’t take anything for granted, so you have to discuss everything, but not in a random way. You put question marks about every choice you make. Each story that you tell is part of the reflection.

So, being critical is crucial?

Yes. This global textbook is the start of the discussion. So, the students or other readers can also discuss the book itself. They should ask themselves “why did they chose that?”.

For example, I was presenting the book when a member of the audience asked, “why did you take the industrial revolution, and why did you take 1870?”. You know, that’s a start. I wouldn’t have had that question if it was another kind of book. With this book people ask, we have a discussion. That’s a good thing.

Another important thing is that global history includes what we call world views. It explicitly includes the question that worlds are not only made by doing something and by conquering something and killing or losing or winning wars.

What happens if you only consider your own views instead of world views?

Then you start writing classic narratives of history. Instead, you have to widen your view and make questions.

We know that Europeans took their ships and sailed to the Americas, and not the other way around. We can regret that, but it happened. Why did the Europeans take the initiative? Here the great thing comes. If you just take it for granted, you’re like “ok, everything starts in Europe, because that’s where we are born”, and you don’t question that. But if you take a more global view and you take a world map then you can see, “oh, Europeans did things differently than Chinese. Chinese had better ships than we had, but they didn’t do that. Why?”

So, it is a matter of perspective. Just ask: “Are these world views? Maybe they’re Western World views. It doesn’t mean they are bad, but they are biased. It is better to explore how different civilizations, different peoples acted. And, then we see deep similarities or differences.

There is another thing. World views are mostly created by the people who ruled. You can have a view as a small peasant, but no one would care. Why do we remember about world views of the Chinese Empire? Because it’s an Empire. Why do we know very little about world views of African people living in central Africa before 1700? We don’t know because they didn’t leave temples and such.

When you question that on a plural point of view, then you discover that you know very little. You don’t ask questions when you only have a linear story about big empires, big states, big people.

World views help to understand that it’s not only about being powerful but also about including alternative views of how the world can be shaped. You don’t have to change the world before rethinking it. Maybe it’s the other way round. You may say we cannot think about something different than capitalism, that the world would go down and everything would disappear. But then you say, “capitalism only existed for 600 years, what were people doing before?”. It’s not an eternal system. So, why cannot we rethink the whole thing? Imagination is so important.

What do you think might be the biggest challenge this book will face?

Maybe two levels.

On a practical level, it’s a challenge for the curricula. Schools have to follow rules and achieve their goals. This textbook might be not fitting as it doesn’t follow classic subdivisions, it asks questions in a peculiar way and that can make it difficult in many countries to be allowed to be used.

So, you worry that even if teachers are willing to use it, they may face some bureaucratic prevention?

Yes.

And the second level is that the book really pushes also the teachers for self-reflection. A teacher that is not willing to do a self-reflection like “what do I teach, why do I teach it, why do I want to know and what is my place there? Am I really wanting to question also my position and my point of view with the students?” cannot use it.

The teacher has to be involved, has to be critical, self-reflective. And if you are a teacher that is like “this is the text and you have to learn it and that’s what I say and if you can repeat it then you are a good student”, well you would be very offended by this book. It’s too critical, it questions too much.

It’s hardly mentioning names. There’s no Napoleon in the book, no Hitler, no Caesar.

So, if you are a student how do you learn about Napoleon, Hitler, Caesar?

I find this a very difficult point. Actually, for you to have a good historical point of view there must be some base line. You need to have a timeline in your head. You need to have to know that the history of capitalism comes after the history of the Roman empire. There are some basic things that you have to know, otherwise you don’t understand. So, this timeline is something that teachers probably have to integrate besides this book. My co-author and I do not teach in middle or high school, so we are actually very curious to find out what teachers think about that. That’s certainly a challenge.

You need to have hard facts in your head. Otherwise you think that facts are not important. Facts, and events, and people are important, of course, because they make history, but they are not in the book and so it could be that extra timeline should be created to tell them the facts. I mean, the French revolution is important, so important, we have to know it’s 1789 and not in the 15thcentury, you have to know that.

-

Be involved!

Are you a student or teacher and would like to take part in Get Up and Goals!?

Follow us on Facebook, subscribe to our Newsletter, keep in touch and be part of our movement to reach the 17 SDGs and spread the Global Citizen Education!